Memorial Stadium Legends and Lore

by Berry Tramel

8/9/2024

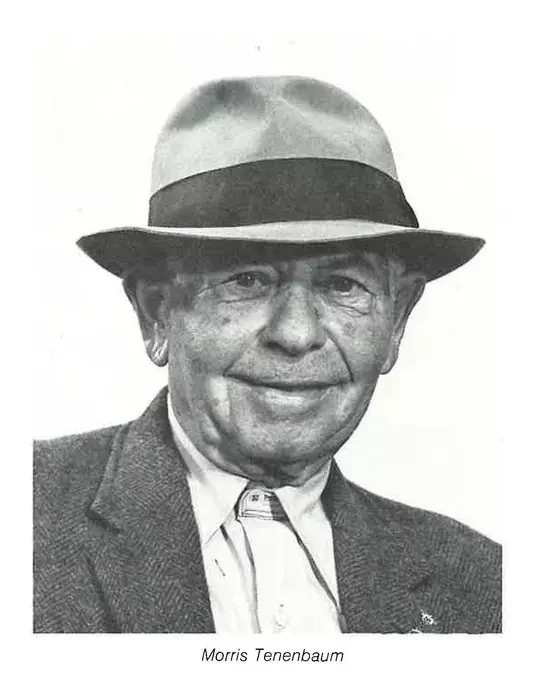

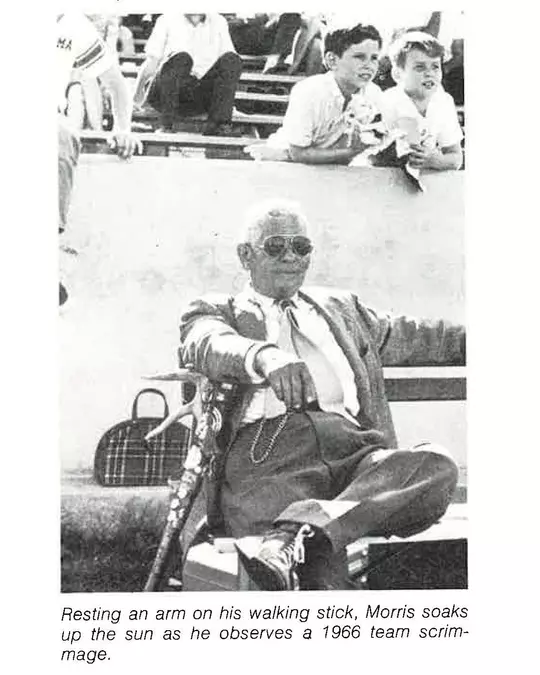

O klahoma Memorial Stadium was built in 1925, and 10 years later, Morris Tenenbaum became the gatekeeper to the Sooner locker room. For games and practices, Tenenbaum served as sentry.

It’s not really clear why Tenenbaum’s services were so necessary. Coaches of a bygone era were not sticklers about closed practices. There were no iPhones capable of shooting quick video.

But either way, Tenenbaum still was on the job. He was at his post every day. He would pass out candy and gum to OU players and coaches, and he would interrogate anyone trying to gain access without proper authorization.

Tenenbaum served as a volunteer. He stayed on the job for 42 seasons.

The Sooners’ venerable home reaches its 100th season in 2024, and the best stories of our athletic shrines are not about brick and mortar. They are about people. Or at least living things.

Morris Tenenbaum and Mex the Dog. The RUF/NEKS and the mass exodus to O’Connell’s Irish Pub. Little Red and the Sooner Schooner.

The history of Owen Field and Gaylord Family – Oklahoma Memorial Stadium is more than the story of legendary coaches and iconic players. Make it to 100, and a venue teems with tales to tell. And for the grand old stadium that has become the Palace on the Prairie, there’s no better place to start than with Morris Tenenbaum.

Born in 1897 Russian Poland, Tenenbaum migrated to the U.S. as a teenager. He enlisted in the Army and fought in World War I, then volunteered extensively for the USO during World War II. Tenenbaum came to Oklahoma City in 1913, settled in Norman in 1923 and opened a second-hand clothing store on Main Street during the Depression. He became legendary among the students in the Greek houses, who discovered he was a willing buyer when they needed spending money.

But Tenenbaum became mostly known for his allegiance to OU football. For 42 seasons, from the Biff Jones era into the early Barry Switzer days, Tenenbaum manned the gate to the locker room.

“Morris has become as much a part of OU as the South Oval and Campus Corner,” Sooner Magazine wrote in 1966.

Morris has become as much a part of OU as the South Oval and Campus CornerSooner Magazine, 1966

Tenenbaum’s upstairs apartment in the stucco house on the northwest corner of Brooks Street and Classen Boulevard contained photos of Bud Wilkinson, Tom Stidham (OU’s coach from 1937-40) and Cliff Speegle, who eventually was Oklahoma A&M’s coach but was a standout end on Stidham’s Sooner teams.

In a heavy European accent, Tenenbaum would ask players “Hey, fraternity brother, want some sleeping pills?" He would toss the player a piece of hard candy, then say, “Vow get on outta here!”

OU players from Cactus Face Duggan to Joe Washington passed through with Tenenbaum’s permission.

In 1954, the university made Tenenbaum a member of the O Club, the lettermen's association.

Ironic, considering he didn’t even like football. “I don’t care about football,” he once said. “I just come out and give the boys gum every day. I like them, and they like me.”

In ’66, Tenenbaum even was awarded an “office.” OU quit using the old wooden ticket booths inside the stadium, and one was fixed up for Tenenbaum, just outside the gate over which he stood sentry.

Tenenbaum was so resolute, he once denied Red Grange entry. If the Galloping Ghost is turned away, what chance did mere mortals have?

Tenenbaum died at age 80 in 1977, and these days OU’s football practices and games are monitored by fingerprint security systems and professional security guards. But they don’t say “Vow get outta here!,” and they don’t have an office in a vintage ticket booth.

More tales of a 100-year-old stadium:

Mex the Dog

OU’s first mascot was a veteran of the Mexican Revolution: a tan and white terrier, dressed in a red sweater and a cap with a white embroidered “O”.

The military company of medic and eventual OU student Mott Keys found the dog among an abandoned litter of puppies near the Mexican border in Laredo, during the Mexican Revolution in 1914.

Keys brought Mex to Norman, where the canine took up residence in the Kappa Sigma fraternity house.

Mex was a dual-threat mascot. The dog both entertained, catching hedge apples thrown by spirit-squad members between quarters, to the crowd’s delight, and serving as a field guard against stray dogs. Mex was famous for running off bigger dogs who would venture onto the field of play, both on Boyd Field, the Owen Field predecessor, and in the new stadium, which was not dog-proof.

Mex was OU’s official mascot from 1919-28. Mex died in 1928. University classes were suspended for his funeral, and he was buried somewhere just north of Owen Field.

Mex was succeeded briefly by Ruf-Tuf, a bulldog who served as mascot for three football seasons starting in the fall of 1928. Boomer, a brindle pup who was nimbler and more adept at tricks, came along in 1929.

More Mascots

From 1957-70, OU’s mascot was Little Red, a dancing Native American. Some American Indians danced on the sidelines before ’57, but usually as part of the Pride of Oklahoma band.

But student protests began in the 1960s over Little Red, and he was officially removed as mascot in 1970 and gone from the sidelines after 1973.

These days, of course, the Sooner Schooner is the mascot most associated with Owen Field. The Schooner has been the official mascot since 1980, but it first appeared in the early 1960s, when the Bartlett family of Sapulpa began sending the Conestoga wagon and ponies to Norman.

The Schooner is driven by RUF/NEKS, the university’s spirit group since 1915, and RUF/NEK drivers in the 1980s and 1990s provided great entertainment. The Schooner always took a tour to midfield after OU scored, but the exit was dramatic. RUF/NEK drivers would stand while heading for the small tunnel in the northeast corner of the stadium, at a fairly fast clip. Drivers would wait until the last possible second to dip their head down and avoid the stadium wall.

Alas, for safety reasons, drivers no longer are allowed to stand, and the Schooner doesn’t travel at such a quick pace. A couple of on-field wrecks will bring more scrutiny.

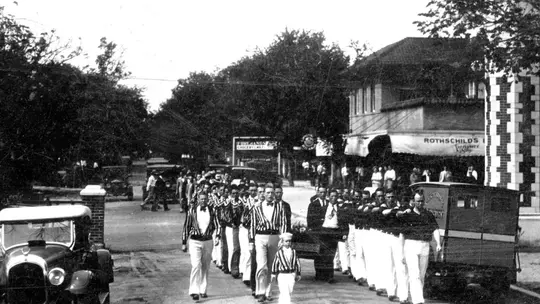

Speaking of RUF/NEKS, they have been around since the stadium’s inception. Founded in 1915, the RUF/NEKS claim to be collegiate sports’ oldest male spirit group. They got their name from an elderly female fan, who griped about the noise they were making at a basketball game. She called them “roughnecks,” and the male students took it as a compliment and ran with it.

By 1921, the RUF/NEKS began carrying red-and-white paddles, and soon enough they were mainstays at the new stadium, taking care of the Big Red Rocket, Cecil Samara’s 1923 Model-T; firing off shotguns in pregame festivities and after OU scores; and collectively sliding into the goal post to recite a chant.

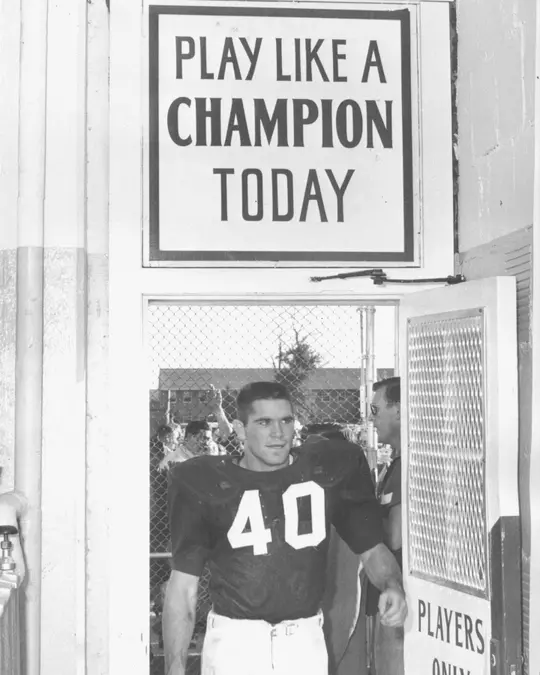

Play Like a Champion Today

Sometime early in his 17-year run as the OU coach, Bud Wilkinson ordered the sign hung up in the tunnel leading onto Owen Field. “Play Like A Champion Today.”

It became a Sooner tradition. OU players still tap the program’s “Play Like A Champion Today” sign on game days as they leave their hype tunnel right outside the locker room, but the sign is much more horizontal in shape than the original.

Trouble is, Notre Dame claims the same tradition. Lou Holtz had the Fighting Irish sign hung in 1986; he said he saw a photo showing the sign hanging in the Notre Dame locker room and wanted it restored.

So who gets credit for the Play Like A Champion Today tradition? Just know this. Those words have been hanging in Oklahoma Memorial Stadium for about three quarters of a century.

?????????????? ?????????????????? 8??3?? » Oct. 4, 1947 | In head coach Bud Wilkinson's first game at Memorial Stadium, the Sooners defeated Texas A&M 26-14. OU's "Play Like a Champion" sign debuted outside the locker room, nearly 40 years before Notre Dame began a similar… pic.twitter.com/4yEmmfOBeV

— Oklahoma Football (@OU_Football) June 8, 2024

O’Connell’s Exodus

Not all traditions are sustainable. For decades, OU fans, particularly on the east side, left the stadium and walked southeast, a block to O’Connell’s Irish Pub & Grill.

The landmark bar opened in 1968 near the corner of Lindsey Street and Jenkins Avenue, and thousands of OU fans made O’Connell’s a game-day stop. Many of them made it a halftime tradition.

OU allowed patrons in-and-out privileges, and many took advantage to partake of adult beverages at halftime. Some didn’t return, considering the Sooners often had control of the game after two quarters.

But in 2005, halftime passouts were discontinued. And soon enough, it didn’t matter. OU bought out O’Connell’s and other businesses to build Headington Hall, which opened in 2013. O’Connell’s moved to Campus Corner, a couple of blocks north of the stadium, and remains a game day staple. But it’s not the halftime magnet it was for decades, when the stadium didn’t serve beer and fans were allowed to leave and return.

Other Sports

For many years, Oklahoma Memorial Stadium was the home of OU track. Both indoor and outdoor.

Like many stadiums built in the first half of the 20th century, a track circled Owen Field. That track was eliminated, and Owen Field was lowered by six feet, in 1949.

But track didn’t disappear from the stadium. Pneumonia Downs, a quasi-indoor track under the eastside stands of Memorial Stadium, was home to Sooner indoor meets into the 1980s. The late Ed Frost, an OU athletics historian, once viewed an indoor meet at Pneumonia Downs and “froze in the process,” he said.

Pneumonia Downs was cold and drafty and not at all conducive to indoor athletics. But walk through the southeast bowels of the stadium today, and you still can make out where some OU indoor track was contested.

It’s the same part of the stadium where a second-floor apartment was squeezed into a corner, for an athlete or two who would do laundry for part of their scholarship. The apartment is long gone, but the ghosts of the pre-palace days remain.

And until 1982, the OU baseball program played at Haskell Park, just beyond the southwest gates of Memorial Stadium. Haskell Park stood on what now is part of the OU football practice fields and where some of the Switzer Center now stands.

The stadium provided some bird’s-eye views of Sooner baseball.